Regulatory reform - deregulation versus better regulation

Simon White | This article argues for better regulation rather than simply less regulation.

It seems that government’s around the world are paying greater attention to regulatory reform. While reform is a continuous activity of all governments, more and more are becoming aware of how the accumulation of regulation can quash business growth and constrain economic competitiveness. It is interesting to see the ways these reforms are being introduced and the potential savings governments claim will be made. However, among these crusades, there is great danger that can undermine the value of good regulation. The removal of environmental regulation, which some are calling “green tape”, is being parcelled up in the name of relief for small business. Is this going too far?

It seems that government’s around the world are paying greater attention to regulatory reform. While reform is a continuous activity of all governments, more and more are becoming aware of how the accumulation of regulation can quash business growth and constrain economic competitiveness. It is interesting to see the ways these reforms are being introduced and the potential savings governments claim will be made. However, among these crusades, there is great danger that can undermine the value of good regulation. The removal of environmental regulation, which some are calling “green tape”, is being parcelled up in the name of relief for small business. Is this going too far?

In Korea this month, the government announced it will cut the total number of regulations on business activities to 80 percent of the current level by 2016 through its Deregulation Drive. The plan was unveiled during a seven-hour marathon meeting led by President Park Geun-hye on national television and translates into the removal of 2,200 regulations and a drop in the total from more than 15,000 to just over 13,000. This is considered important to spur greater levels of economic growth in Korea.

On 28 March, Finance Minister Hyun Oh-seok presided over the first ministerial-level meeting on the matter to inspect, evaluate, and come up with follow-up measures to President Park Geun-hye’s three-year economic innovation plan. They pinpointed 52 regulations that could be improved. Hyun said 41 of the regulations can be addressed immediately, with 27 of them to be amended in the first half of this year.

This site contains an interesting interview on Korea’s reform efforts with Dr. Kim In-chul, professor of International economics at Sung Kyung Kwan University. He talks about creating the right incentives for reform and how the government as learned from the previous government’s attempts at regulatory reform. He also describes the adoption of the “one-in, one-out” system or the “regulation cap” and the use of sunset clauses.

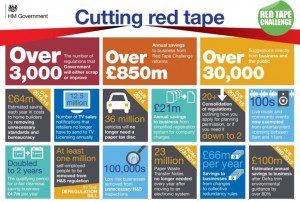

Last year I reported on some the the UK government initiatives in this field, which included the Red Tape Challenge. The RTC is gaining momentum. Some 3,000 pieces of regulation have been identified for action. They will either be improved or scrapped. An Excel document containing this list can be downloaded from here. David Cameron’s announcement can be found here.

So we have trawled through thousands of pieces of regulation – from the serious to the ridiculous, and we will be scrapping or amending over 3,000 regulations – saving business well over £850 million every single year. That’s half a million pounds which will be saved for businesses every single day of the year.

The infographic below promotes the savings of cutting red tape.

In Australia, the new Coalition Government has introduced Repeal Day. See the government’s Cutting Red Tape site. Two Repeal Days will be held each year. The first was on 19 March 2014 and the second will be during the Autumn session of Parliament. When introducing the initiative into Parliament this month, Prime Minister Tony Abbott said the red tape repeal would remove 9,500 “unnecessary or counter-productive” regulations and 1,000 redundant acts of Parliament. “Removing just these will save individuals and organisations more than $700 million a year, every year,” he said. The Liberal Party’s own policy document on regulatory reform will save one billion Australian Dollars annually.

The use of parliamentary sitting days for the repeal of legislation and regulation has been used in other jurisdictions to repeal redundant or unnecessary legislation. In the United States, the House of Representatives holds repeal days that are known as the Corrections Calendar. The Corrections Calendar contains a list of bills that focus on changing laws, rules, and regulations that are judged to be out-dated or unnecessary. These bills are considered by the House of Representatives and debate is limited to one hour. For a bill on the Corrections Calendar to pass the House of Representatives a three-fifth majority vote of those present is required. In Australia, the first repeal day was organised by the Western Australian Government on 8 November 2012, which was used to repeal five acts from the statute book.

Later this year, the Australian Senate will debate the Omnibus Repeal Day (Autumn 2014) Bill 2014, available here. This Bill, which was passed by the Parliament this week (on 26 March 2014) is described as:

a whole of government initiative to amend or repeal legislation across ten portfolios. The Bill brings forward measures to reduce regulatory burden for business, individuals and the community sector that are not the subject of individual stand-alone bills.

There are two questions that arise from this growing push for regulator reform. The first is: Does business actually benefit from these reforms? The second: Are red-tape reduction strategies being used to remove good and proper regulation?

Does regulatory reform help business?

The red-tape reduction initiatives described above are all justified by the savings they will produce for business and consumers. There is no question that, in most countries, there are too many regulations, often old and outdated, but also unnecessary and inefficient, that increase the cost of doing business and that these increases have a broader influence on competitiveness. Campaigns that aim to identify and remove these are important and necessary. However, it is easy to get caught up in a public relations exercise that imply all these regulations have an equal influence. For example, a recent article by Peter Martin, the economics editor of The Age newspaper in Melbourne, quotes Professor Fred Hilmer, former chair of the National Competition Policy Review Committee, and author of the “Hilmer Report” – the 1995 National Competition Policy.

“I’ll give you a silly example,” he said referring to his own experience as vice-chancellor of the University of NSW. “Under the Audit Act, a university has to file accounts to the Parliament for every one of its subsidiaries. That would be a book centimetres thick. We don’t. No one does it. And they’ll repeal it. “

While removing useless, unenforced regulation is not a bad thing to do, as Peter Martin says, “removing laws that cause actual damage is harder”.

John Wanna from the Australian National University similarly describes deregulation exercises as “smoke and mirrors”:

Parliament is unrelentingly cranking out thousands of new amendments and regulations each session, yet governments will periodically want to appear to be reducing the regulatory burden on the community and especially business – as a productivity measure. Reporting requirements, compliance frameworks and other accountability impositions are increasing at a far faster rate than any rolling back of out-dated regulations… There are some big deceptions behind the Abbott-Frydenberg initiative. One is that they claim the abolition of these regulations sitting on the statute books will miraculously save millions of dollars and make us more competitive. Yet most of the ones destined for abolition are truly anachronistic laws and regulations (some decades and even centuries old) that hardly apply to modern business.

The take home of all this is that while red-tape reduction is a good thing, the repeal of old and out-dated laws and regulations is a normal part of the work of parliaments and governments. While thousands of laws and regulations will be removed or improved, the challenge is to focus efforts on those that have the most impact on business and the economy. In the Australian instance, many of the problematic laws and regulations faced by business are created by local and state governments. These will not be affected by the Federal Government’s Repeal Day efforts.

Cutting what we shouldn’t – the chaining colour of tape

The second question I’ve raised concerns the danger of using regulatory reform campaigns to remove or alter regulation that serves a useful purpose. A case in point is regulation that protects the environment.

Whether by design or accident, red-tape reduction is now including so-called “green-tape”. The Australian Government’s reform programme consistently uses the term “red and green tape”, as does the Coalition policy. Similarly, in the UK’s Red Tape Reduction campaign, the British Prime Minister announced that by this month next year the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs “will have slashed 80,000 pages of environmental guidance saving businesses around £100 million per year”.

While environmental regulation should not be excluded from assessments that might improve its effect and efficiency, there appears to be a danger that the scope of a general deregulation agenda is widening. All regulation, whether good or bad, imposes a cost on business. All costs are not bad. The purpose of deregulation should not be to remove as much regulation as possible, but to balance the cost on business with the benefits to the broader community and the environment.

Another regulatory issue that is possibly affected by the deregulation push in Australia concerns gender audits. Beth Gaze, from the University of Melbourne, is concerned that the requirement for employers to report on the gender makeup of their workforce could easily fall victim to a deregulatory agenda. She describes how the Workforce Gender Equality Act of 2012 requires employers to provide annual information on several “gender equality indicators”, including the gender composition of the workforce and governing bodies such as councils or boards of directors; pay equity between women and men in the workforce; and the availability and use of flexible working arrangements for male and female parents and carers. Pay equity data shows the current pay gap between men and women is 17.5% and has consistently been between 15% and 18% over the past two decades. This suggests that little or no progress has occurred in moving towards workforce gender equality.

“Is reporting by employers unjustifiable and wasteful red tape?” asks Gaze. It applies only to employers of more than one hundred people and not to small businesses.

Do the benefits of reporting justify the extra time and effort? Information on an employer’s workforce and how it changes from year to year allows both assessment of the employer’s progress on gender equity, and identification of effective practices. This knowledge is not available from anywhere else and is essential to understanding both progress and the barriers to progress in gender equity at work. Reports will give shareholders, employees, job seekers and the public a concrete view of whether a company’s expressed commitment to gender equity at work has led to improvements in practice.

While this legislation has been in the government’s deregulation sights, government currently indicates it will delay these changes and consult further.

There are substantial benefits to be gained from a regulatory reform effort that reduces the burden of unnecessary and onerous regulation on business, while improving the quality and efficiency of the regulation we require. The term “red tape” is typically used to describe excessive regulation or rigid conformity to formal rules that is considered redundant or overly bureaucratic. This does not apply to all regulation. Most regulation exists for good reason and while it might need updating from time to time, it should not be thrown out with the proverbial bathwater.

The greatest challenge in all this effort it to identify those barriers that have the greatest impact on economic performance. This is where the full benefits of reform can be realised.